| © European Voice 2010 vom 15.07.2010, S. 10 |

Grown-up Anarchist

ein Porträt von Constant Brand

Rebecca Harms, the coleader of the Green/European Free Alliance group in the European Parliament, has become a de facto German ambassador to Greece during the country’s debt crisis. She has been shuttling between the two countries at her own initiative, prompted by the backlash against ethnic Greeks in Germany because of the bailout of Greece.

It is an initiative, much of it done at a community level, that echoes Harms’s start in politics, as a grassroots campaigner. And its low profile is perhaps in keeping for a politician who remains little-known outside environmental circles. Compared with Green leaders such as Cem Özdemir and Jürgen Trittin, the 53-year-old Harms is little-known, as she freely admits.

|

| © European Voice 2010 |

She is the less conspicuous part of the Greens’ traditional male-female leadership duo in the Parliament, alongside Danny Cohn-Bendit. The two are very different. Both are workaholics, but, according to party colleagues, Harms is a more measured and pragmatic political animal than Cohn-Bendit. He likes to shoot from the lip; Harms, by contrast, is “a listener, outgoing and engages colleagues”, as one colleague puts it. And while Cohn-Bendit’s political views emerged from France’s student protests in 1968, Harms’s attitudes were shaped by the early anti-nuclear movement in Germany.

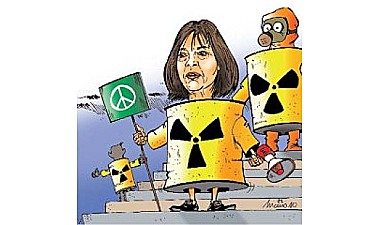

Harms attributes her strong, often passionate, views on the environment, European unity and her opposition to nuclear power to her upbringing and activist youth as, in her word, “an anarchist”.

Born in 1956 into a traditional working-class household in post-war West Germany, Harms grew up in a village close to the city of Uelzen, in Lower Saxony. Her father, who drove a milk lorry for a living, and her mother, who stayed at home to raise Harms and her two siblings, wanted her to go to university, but she followed her love of plants and the countryside and chose to become a landscape gardener. During her apprenticeship years, she moved with like-minded friends to an abandoned farm in the nearby district of Lüchow-Dannenberg and joined a local organic farmers’ co-operative. They were part of the broader left-wing, ecological movement sweeping parts of the then West Germany. Nonetheless, she says, it was chance that led her to join the antinuclear movement. One evening in 1977, when she was 21 and still an apprentice, the boss of her garden centre drove her to a meeting launching a community campaign to fight plans by Lower Saxony’s state authorities to build a nuclear-waste storage centre in salt mines in nearby Gorleben, a forested site close to the Elbe River.

Harms was tasked with forging an unlikely alliance of left-wing activists, communists, hippies, local dairy farmers and village residents. In May 1980 and with the campaign in full swing, the 23- year-old Harms joined plans to set up the ‘Free Republic of Wendland’, whose capital was a protest camp of makeshift huts on one of the possible storage sites. A month later, the authorities sent in riot police, bulldozers and helicopters. The protest was crushed, but “in the end we managed to get the attention of all of Germany”, says Harms. “It was a typical David versus Goliath action. It was a lesson in successful non-violent action; all citizens were with us against the state. It felt like war.”

During the campaign, Harms struck up a friendship with Undine-Uta Bloch von Blottnitz, a local landowner from an aristocratic family who, like Harms, had become one of the movement’s leaders. When von Blottnitz became a Green MEP in 1984, she asked Harms to become her assistant. Harms had just begun several literature courses at Hamburg university, though she still lived in the co-operative. “At that time I had 40 goats, so I still had my other life, so I was not sure I could combine it, but the offer was so attractive,” says Harms, who speaks English with ease and turns to French when English words elude her. “When I arrived in Brussels and Strasbourg, for me it was a perfect study period, much better than at university”.

Over the next four years, Harms cut her teeth on the issues she now concentrates on: renewable and nuclear energy policies, consumer protection and ecology. She also focused attention on the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, an event that crystallised her belief that environmental problems – not just nuclear issues – need to be addressed at an international, and not just at a regional and national level.

But the constant in-fighting of the nascent Green party in the still young directly elected European Parliament sickened Harms and, in 1988, she returned to Germany to work as a production manager at the Wendland Film Co-operative, producing, among other films, documentaries about the Gorleben protest movement. Interim facilities have now been built to store radioactive waste, but the site remains a focal point for environmentalists, with thousands of activists coming to the area every year to stop deliveries.

Harms’s break from politics lasted six years, until she was recruited by the Greens in 1994 to run (successfully) for a seat in Lower Saxony’s state parliament. She became the party’s leader in the state assembly in 1998 and became active nationally as well, joining the party’s federal council in the same year.

Her personality is quiet but strong, and she became a powerful behind-thescenes national player. By 2004 she was important enough to head the German Greens’ list in elections to the European Parliament. When she stood to be coleader of the Greens, a less fractious party now than in the 1980s, she was approved unanimously.

Colleagues say she is a tireless leader, particularly about the risks posed by poorly built nuclear reactors, which has led her to focus, for example, on the need to close Bulgaria’s Kozloduy power plant. She has also spoken out loudly against EU funding for the experimental International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) fusion project, money that, in her view, would be better spent on research into renewable energy.

Harms, whose husband works as a local film-maker in Germany, says she has no ambitions to enter national politics, adding she is so busy now she hardly has time for her garden in Lower Saxony, reading or cinema, let alone to jog as much as she would like. “In Europe, I am a smaller star, but I like that,” she says.

CURRICULUM VITAE

1956: Born, Hambrock bei Uelzen

1977-84: Co-founder of a group opposed to the construction of a nuclear waste storage site in Gorleben

1979-84: Qualified as a nursery and landscape gardener

1984-88: Assistant to German Green MEP Undine-Uta Bloch von Blottnitz 1988-94: Film production manager, Wendland Film Co-operative 1994-98: Member of the Lower Saxony regional assembly

1998-2004: Leader of Greens in the Lower Saxony regional assembly; member of the Greens federal party council

2004-: Member of European Parliament 2009-: Co-leader of the Greens/EFA in the European Parliament